From our colleagues at NYP’s Advances

Growing up in New Jersey as the son of Greek immigrants, Dr. Steven Stylianos never imagined he would become a doctor. But the seed was planted after his high school guidance counselor told him — much to his surprise — that he would make a great physician one day.

“My vision for myself didn’t go beyond what I was doing over the next weekend,” says Dr. Stylianos, Chief of the Division of Pediatric Surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia and Surgeon-in-Chief at NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital. “I had no professional role models, so what she said to me really sent me on the pathway to medicine. I’m so grateful this journey has led me to where I’m supposed to be — operating on children and trying to give them a fruitful life ahead.”

The father of three has done just that over a nearly four-decade career. Dr. Stylianos’ goal has always been simple: to help kids. His mentors were the ones who recognized he had the traits of a successful surgeon, like an analytical mind and the ability to focus under pressure. Over time, those skills helped him build an expertise in pediatric trauma care and complex surgeries like the Kasai procedure, a treatment for infants with biliary atresia that slows the progression of liver failure. He’s also helped separate five sets of conjoined twins, most recently in 2020 as part of the team that separated 5-month-old twins from Sierra Leone.

Dr. Stylianos spoke to NYP Advances about the lessons he’s learned over the course of his career, the power of mentorship, and the legacy he hopes to leave behind.

How do you prepare yourself before taking on high-risk, complex surgeries, like the separation of conjoined twins?

Just as important as the technical skills is the mental planning behind making sure you’re prepared for different scenarios and outcomes. When you’re dealing with conjoined twins there are so many anatomical issues that need to be sorted out with a larger multidisciplinary team, as many twins share too many vital organs to survive apart. So first we need to decide if we can even move forward with a separation. With our most recent case, the Jalloh twins, we determined we could separate the twins because even though they shared significant portions of their liver and abdominal wall, they had separate strong hearts. Then we have multiple discussions to map out the different parts to the surgery to make sure everyone’s prepared for their role. The more talented the surgical team the better the outcome is going to be, and I’m lucky to work with such talented teams.

For me personally, whenever I’m working on any kind of complex surgery, I like to break it down into its manageable parts so that it feels less overwhelming. I work through a best-case scenario and a worst-case scenario, and I have a plan for abnormalities that might not be visible on an X-ray. I think of it using a baseball analogy: a surgeon is like a batter who must be ready to hit any one of four pitches. So going through this preparation gives me both the comfort and confidence that I’m giving a patient my best before I walk into the OR.

What drives you to continue pushing the boundaries in your field?

One of the most powerful moments is when a family hands you their child and says, “Please save my baby.” I never tire of that privilege and that responsibility, and it keeps me coming to work every day. One of the incredible joys of being a pediatric surgeon is that because you operate on infants, you get to watch them grow up. You get updates on their graduations, their marriages, and when they become parents. It’s funny to think that you were once a stranger to them, and suddenly you become one of the most important people in their lives and a part of their family. That’s the legacy I’m leaving behind, and I’ll keep doing this until my hands or eyes don’t work anymore.

You recently started a peer support program for five surgical departments at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia. Why did you think that was important to do?

When I think back to my training and my early career as an attending, there was little attention paid to the wellbeing of physicians. When things didn’t go well in the operating room or you lost a patient you had treated for years, it was devastating, but there was nothing to help process the events. You would just show up at work the next day and try to do your best to take care of another family, even if you were suffering inside. Our patients and families may see us as superheroes, but we are human, with the same emotions and vulnerabilities as everyone else.

Now, there’s more focus on the mental health of physicians, and the peer support program is an acknowledgment that we can take better care of each other. We have faculty and residents who have received training and will proactively reach out to a surgeon after an event occurs and say something like, “Hey, I heard you had a tough day in the OR yesterday. Did you know we have a peer support program that has been helpful to others? Would you be interested in a phone call?” Surgeons don’t like to show weakness, so it’s not a reflexive reaction for them to reach out if they need help. This proactive approach allows them to get help in real time rather than suffer on their own. We’re happy to do this because we want our surgeons to be healthy and at their best when they’re taking care of patients.

What are some words of advice you give to doctors just starting out?

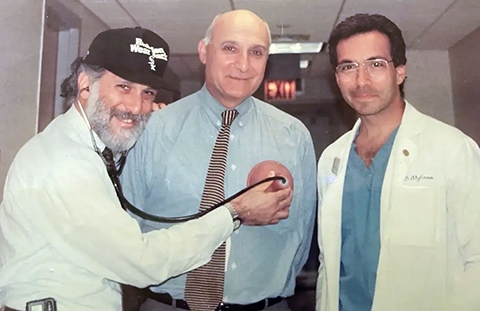

Very early on in my own career, I recognized that if a mentor pays attention to you, you embrace that relationship. To this day, when I do the Kasai procedure, I still think of my mentor and predecessor Dr. Peter Altman, who championed the procedure in the U.S. He always wanted us to be courageous and thoughtful and push the envelope.

I also advise making decisions about where you want your career to go by asking yourself two questions: Which patient population do you want to spend time with for the next 30 years, and which diseases do you really want to fight against? By answering those, you’re making a difficult choice much less intimidating.

Finally, I would remind young doctors that the best physicians are the ones who remain grateful and understand what a privilege it is to help ease the suffering of your fellow man. Medicine is a noble profession, and no matter what hardships you go through or how many years it takes, it’s all worth it if you maintain that perspective.

What is most rewarding about working at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia?

It’s the combination of working at a great hospital and a great university. I’ve found my way back here twice, which not only helped bring me back to family but also gave me the opportunity to work with my mentors as partners. Even now when I come into my office, I always think that I’m opening Dr. Altman’s door, and I just happen to be the one who sits here now. Through my leadership positions, I like to think that I’m paying back those mentors who invested in me by training the next generation to go on and do great things.

Related

- From the O.R. to the ICU, 25 Years Later It’s Still a Family Affair for Sibling Duo in Pediatric Surgery

- Teach Them Young: Lemonade Stand Raises Money for Sick Kids at NYP/Columbia

- Bringing Life Saving Heart Surgery to Children in Nigeria

- Tiny Patients, Big Solutions: A Closer Look at Fetal Surgery Innovations