Heart surgeon and Chairman of the Department of Surgery, Craig Smith, MD, has never been particularly interested in spectacle.

If you’ve spent time around him, what stands out is not flash or pomp, but discipline. Precision, humility. A way of looking closely at things, whether those things are hearts, sentences, photographs, or ideas, and deciding what actually matters. His memoir, “Nobility in Small Things: A Surgeon’s Path,” demonstrates that attunement throughout all stages of life.

Innovation, in Dr. Smith’s world, has rarely announced itself loudly. It has arrived thoughtfully, incrementally, and with purpose.

“Surgery is really a performing art,” he said, not in the sense of showmanship, but in the sense that it requires judgment, restraint, and the ability to respond in real time when things don’t go as planned. It is art informed by science, not the other way around.

That philosophy has shaped everything from how he operates to how he teaches to how he has led one of the country’s largest and most complex academic surgery departments.

The Craft Comes First

In the short video above, Dr. Smith demonstrates how to tie a surgical knot. On its face, it is a technical lesson, but in viewing, it reveals something a bit larger.

“Shorten the lever,” he echoes in a subsequent Grand Rounds reflection. “Rest your forearm, your wrist, or the underside of your palm somewhere. The shorter the lever, the more control the movement at the end of the lever.”

The lesson is not about speed or flair. It’s about control; understanding the physics of what you’re doing, the forces at play, and the consequences of carelessness. In surgery, he has often said, fixing the problem matters far more than how quickly you move. “If you fix the problem," he noted, “remarkably long cross-clamp and bypass times can be tolerated. Conversely, if you don’t fix what’s broken, speed won’t save you.”

These ideas recur throughout his career, not just in how he operates, but in how he evaluates new techniques and technologies. For Dr. Smith, innovation is not something to be chased. It is something to be earned.

Read More: The Culture Consult: Dr. Craig Smith on What He’s Been Reading Lately

Stealth Innovation and the Long View

When asked about the most futuristic thing happening in surgery today, Dr. Smith’s answers have always resisted easy headlines. Tissue engineering holds promise, he’ll say, but much of it is still aspirational. Robotics has finally matured, not because it suddenly does new things, but because it now does many things better, more consistently, and in more hands.

Most improvement, in his view, does not come from seismic breakthroughs. It comes from what he’s called stealth innovation, small, cumulative advances that only reveal their impact over time.

“You look back twenty years later,” he observed, “and you can’t recognize where you are.”

That long view has also made him skeptical of hype, particularly around artificial intelligence. AI may transform medicine, he has acknowledged, especially in cognitive specialties like radiology, but surgery is different. It is heterogeneous, tactile, and deeply human. There is no algorithm that can replace judgment at the operating table.

Even robotic surgery, he’s quick to point out, is something of a misnomer. “The robot is not a robot,” he likes to say. What we call surgical robotics is a controller–responder system: a machine that translates analog human movements into digital signals, then back again. The intelligence remains human. Always has.

Read More: State of the Union: The Stealth Innovations of Modern Surgical Care

Leadership Without Performance

Dr. Smith did not set out to be a department chair. “I didn’t think of myself as a leader,” he has said plainly. Leadership, for him, was not an aspiration but a responsibility, something that emerged as his career unfolded, rather than something he sought out.

That sensibility has defined his tenure. He has never led with a manifesto or a grand theory of administration. Instead, he has relied on instinct, judgment, and a willingness to act decisively when necessary, and to wait when it wasn’t.

“Some of the most important times to project confidence,” he reflected, “are when you don’t actually have it.”

That tension between decisiveness and humility, confidence and uncertainty is one he has never tried to resolve neatly. In fact, he’s often argued that it shouldn’t be resolved at all.

Watch the 2025 commencement address Dr. Smith delivered at his alma mater, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine:

COVID and the Power of Plain Speech

If there was a moment when Dr. Smith’s leadership style became visible far beyond the walls of the hospital, it was during the earliest months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Information was scarce. Guidance shifted daily, and fear was pervasive. “Information was a salad of confusing rumors, rambling emails, and pronouncements from multiple sources,” he later wrote. So he did what felt necessary and began writing daily memos to the department, bringing clarity to chaos.

What began as internal communication quickly became something else. His updates acknowledged uncertainty rather than papering over it. They resisted platitudes. They spoke honestly about fear, exhaustion, and the weight of responsibility. Because of their immediate impact internally, we felt compelled to share them with the public.

“I sensed that people sharing such universal dislocation needed morale as much as information,” he wrote.

Those memos eventually found a much wider audience, not because they were polished and beautifully written (which they were), but because they were human. They demonstrated a kind of leadership that valued transparency over posturing, and trust over reassurance theater.

One line, in particular, came to define that moment: Nobility in small things will get us through this.

It was not meant as a slogan. It was an observation, one grounded in watching people show up, day after day, in classically unremarkable but essential ways.

From the Wall Street Journal: The Pandemic’s Most Powerful Writer Is a Surgeon

Confidence, Risk, and Responsibility

Throughout his career and in his memoir, Dr. Smith has spoken candidly about confidence. Not as bravado, but as something fragile, earned, and easily lost.

“Confidence,” he has said, “is only measurable as a ratio of confidence to competence. And that ratio should always be hovering around one.”

Too much confidence without competence is dangerous. Too little confidence, even in capable hands, prevents people from reaching their potential. The balance is never stable; everyone wavers.

As his daughters once dubbed ‘Dad’s Law,’ he says: “Nobody has confidence who hasn’t lost it and regained it.”

This perspective has informed how he talks about risk, accountability, and failure, especially in a field where the stakes are impossibly high.

“If you can’t take the lows,” he once remarked, “you don’t deserve the highs.”

Attention as a Form of Care

Outside the operating room, Dr. Smith’s interests have often surprised people because they reveal the same attentiveness he brings to surgery.

Years ago, he began photographing a single Barbie shoe he found under a couch cushion. A small, accidental object that became the subject of a long-running photographic series, placed carefully in natural landscapes, architectural settings, and domestic scenes. What began as curiosity turned into a fun, sustained artistic exploration.

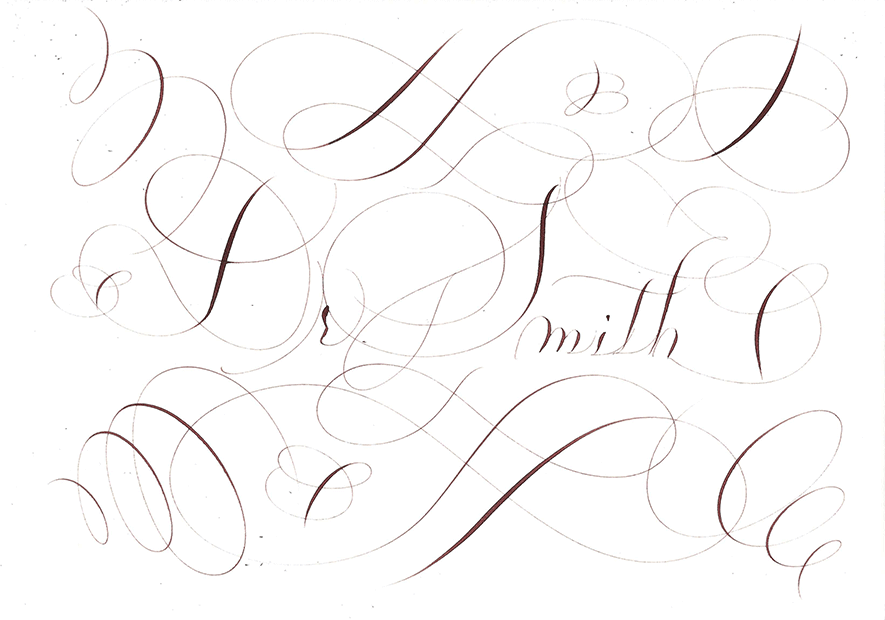

In another instance, a patient, famed calligrapher Bernard Maisner, once handed him a piece of intricate calligraphy as a thank you. Maisner recalls how Dr. Smith studied it carefully, not out of politeness, but out of genuine interest. Later, reflecting on their correspondence, Dr. Smith explained why moments like that matter to him.

“I think it’s important to acknowledge the specifics of what someone sends me,” he said. “The effort they put into it.” That instinct to look closely, to recognize effort, to treat craft with seriousness, runs through everything he does.

What Endures

As Dr. Smith retires from his role as Chair of the Department of Surgery, it would be easy to frame this moment as a conclusion of a truly impactful career in medicine. But endings have never interested him much, either.

What he leaves behind is not a single innovation, policy, or program. It is a legacy of deep and unabiding character, a way of approaching work with restraint, curiosity, and care. A belief that progress is usually incremental. That leadership does not so much require performance but thoughtfulness. That transparency is a form of respect. That small things, done well, matter the most.

Humans, as he has often noted, are imperfect. They will always need care. There will always be a need for surgery, and for people willing to do it thoughtfully. That work continues.

Related:

- Lessons Learned: Surgeon Craig Smith Reflects on Career in the OR

- The Future, Today: Dr. Craig Smith on the Most Futuristic Thing in Surgery

- The John Jones Surgical Society Honors Dr. Craig R. Smith With the Society’s Distinguished Service Award