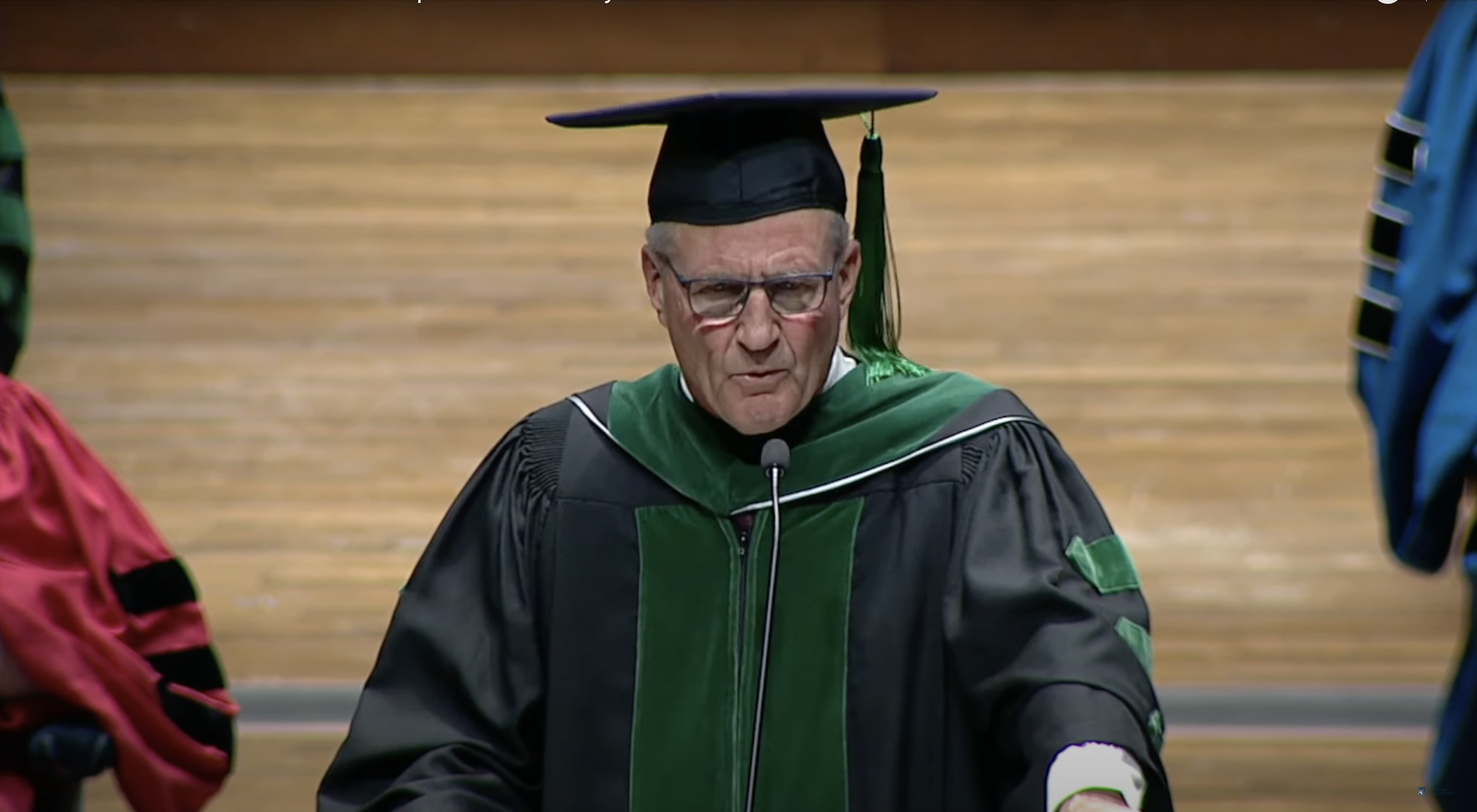

In a speech that moved from the steel mills of Pennsylvania to the fields of Indigenous medicine to even a dystopian android underworld, and back again to the sacred utility of healing, Chair of the Department of Surgery, Craig Smith, MD, delivered the 2025 commencement address at his alma mater, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. With candor, wit, and philosophical heft, Dr. Smith reflected on the pressures facing medicine today, the privilege of being useful, and what it means to enter a profession where your decisions may, quite literally, determine whether someone lives or dies. Below, we share the full video and a transcript of his remarks.

First, the acknowledgement—and I’m quoting from this university’s website: “In recognizing the land upon which we reside, we express our gratitude and appreciation to those who lived and worked here before us.” Recognizing the land upon which we reside, we express our gratitude and appreciation to those who’ve lived and worked here before us. It’s been 48 years since I lived and worked here. Your gratitude and appreciation are more than adequately expressed by granting this ancient ancestor the honor of speaking today to faculty, parents, and family—and especially graduates—on this important occasion in this magnificent setting.

This will be the last commencement ceremony for most of you, as it was for me in 1977. My task today is simplified by the fact that each of you has endured at least a few commencements during your life. I’m sure previous speakers have admonished you to embrace failure and follow your heart, and you’ve already run enough laps in life to have tested those lofty principles.

My last commencement address was to a prep school years ago. The parents gave me a raucous standing ovation when I told the graduates why they should never get tattooed. But I won’t try that again since you’re old enough to live with your choices. But in that vein, since you will be joining me as peers and colleagues at the end of this ceremony, I will address you as such. Peers should expect directness and honesty, which guarantees we won’t always agree, but if I’m not willing to say what I really think, why should you listen to me?

I’ll begin with an old story. In 1984, I spent a month at Stanford observing their pioneering heart-lung transplant program. I bumped into a man who had been a close friend in the early 1970s when he was finishing his MD-PhD and I was pretending to work on a PhD in biophysics. He’d become a tenured professor in immunology at Stanford and was becoming known for some of the foundational science behind an important biotech startup. Over too many drinks one night at a bar in Palo Alto, I asked if he missed taking care of patients. He shook his head without detectable regret and explained, “I’m driven by peer group recognition, and patients are not my peer group.”

Patients are not my peer group. At the time I thought to myself, that’s an interesting way to put it. Isn’t everyone a patient someday? But over the years I’ve come to realize that my old friend had actually captured perfectly the kind of self-referential bubble that underpins the monoculture of contemporary higher education. It’s the attitude that has slowly strangled viewpoint diversity and eroded public confidence in us—because people are no longer our peer group. We’ve abandoned the sweaty marketplace of unanswered questions to lounge in a temple of unquestioned answers.

Now I mention this today because our cloistered monoculture has had much to do with motivating the Trump administration’s intrusion into higher education—an unavoidable topic for anyone in our profession right now. Now viewed most charitably—and I’ll admit this may be Pollyanna-adjacent—perhaps the government wants only to recalibrate the way indirect costs of research are shared. An arguably overdue reconfiguration of what all sides should acknowledge has become a critical codependency.

It is a codependency for the government because NIH-funded research has produced a return on investment that is the envy of the world, while at universities the dependency has become existential, such that even a Solomonic compromise on indirect rates will dramatically change the way many universities do business. For example, the health sciences at Columbia University receive $1 billion in federal funding annually, which is 29% of their operating budget. Dependency on that scale is making it hard for those impacted to see the problem dispassionately.

Our monoculture, bless its heart, believes that good faith is always present on its side of a negotiation and always absent on the other side. Therefore, any flavor of compromise with our federal government is labeled appeasement, capitulation, caving, bending the knee, kissing the ring. “We’re going to lose everything anyway,” the argument goes, “so we might as well go down fighting.” To me, that’s an expression of despair and willed helplessness that doesn’t resonate—but it always draws applause at faculty meetings and clearly makes people feel better.

“There’s not to reason why / There’s but to do and die.” “Into the valley of death rode the six hundred.” Now, I’d rather work towards a mixture of wins and standoffs and fallbacks than gallop off with the Light Brigade. There’s an old saying about advertising that we know it works about half the time—we just don’t know which half. It is critical for us to remind the government that NIH funding is similar, and very importantly, that the payoff from the half that works accounts for our country’s scientific and technological dominance.

Behind the curtain of Harvard’s monoculture-invigorating resistance, reliable sources tell me that there are intensive legal and meta-legal negotiations going on that give me hope for a survivable future. I believe the same is true at Columbia—minus the big bluff.

Now graduates, I don’t pretend to know how this battle will end, or when, or how exactly it will impact your future. But I do suggest adopting a guardedly optimistic long view. I’m aware that the graduates in front of me are mostly the so-called Zoomers of Gen Z. The social science-y witches and warlocks of the media inform me that your generation is lazy, impoverished, socially isolated because of cell phone toxicity, indifferent to procreation, and always on the verge of burnout.

You’re famous for quiet quitting and “resenteeism.” Together, those labels mean you bitterly complain about a job at which you work only hard enough to avoid being fired. A health journalist for New York Magazine recently contributed to this genre in a chatty piece focused on disillusionment inside medicine with the biasing title, “To Become a Doctor, Denial Helps.” An ENT surgeon who was quitting in her 30s deplores the false promise of medicine. A medical student echoes the quiet quitting theme by saying, “Our generation is realizing you don’t have to kill yourself.”

Now I don’t buy all the labeling and catastrophizing, and I hope you don’t. Ennui and crises of motivation were not invented by Zoomers. There were oceans of both among my fellow Boomers in the 1960s and 70s. Actually, I challenge Zoomers to beat my generation at espousing avoidance of hard work in their 20s. Our anthem was, “Oh, what a bummer, man. You’re stressing me out.” Yet many aimless, self-involved Boomers became hardworking, high achievers and have hoarded wealth that may be coming your way someday.

I will respectfully reach across the generational divide and suggest that you at least keep your minds open to being seduced by work. Consider the possibility that real wellness is increased much more by rewards derived from big goals worth achieving than it’s decreased by the difficulty of reaching them. Or put metaphorically, there are destinations that justify any journey.

I pledged at the outset to avoid repeating what you’ve heard from previous commencement speakers—or, God knows, from tech-bro TED Talks urging you to fail fast or move fast and break things. I mean, look at the evidence. Here you sit in Severance Hall, successful and unbroken. It’s possible you will never fail—at least not in the grand, best-selling memoir, viral screenplay sense of the term. That’s all good news. But you are entering a profession in which a life hanging in the balance—quite literally—might depend on you. In that situation, things can come at you very fast.

Here’s a paradox. Although you may never capital-F “Fail,” you’re going to make many, many mistakes. So indulge me in some analogies from baseball. Note for context that baseball is a team sport in which players have very specific individual roles. Professional baseball has kept close track of individual errors for 160 years. The most frequent error-committers in baseball history are shortstops, along with a few second and third basemen. In other words, the best defensive athletes in the game.

Why all the errors? Because of frequency times difficulty. They have the opportunity—I might even say the privilege—of facing the most of the most difficult plays. Now, it’s obvious that the game doesn’t end just because somebody made an error, but that leads me back to the healing sports. If you remember nothing else, remember this: it’s never the first mistake that harms the patient. Harm comes from the next three or four bad decisions that compound the initial error. So when you drop that fly ball or overthrow the plate, keep thinking, keep trying to make the right choices. You’ll be fine. Irretrievable single errors are rare.

Back to baseball—notice that each game is potentially infinite. In the final inning, no matter the score or how the team got there—and even if you sprinkle in a few errors—as long as the team keeps making plays, you and they can still win. In your individual role, just keep thinking, keep trying, stay in the game. Think of yourself as always batting in the bottom of the ninth.

So enough about mistakes and politics and future dread. To bring this to a close, I’ll try to show you what isn’t at risk as you enter our great profession—what will always be there for you. I hope you’ll bear with me in a couple of fantasies. You’ll remember that in my introduction, I selfishly appropriated gratitude from the acknowledgement that is officially aimed at Native American tribes of the Great Lakes. So imagine yourself tesseracted from your seat here today, a couple thousand years back, into a thriving Chippewa village.

The villagers are favorably impressed by your tribal regalia and your funny hat, and welcome you into their community. A few days later, the village healer asks for help with a man who’d been ambushed by enemies while pulling steelhead out of the Cuyahoga River. You’re led to the victim’s wigwam. The man has fever, delirium, and a suppurating tomahawk wound in his thigh. You make a vat of detergent solution by collecting baskets full of buffalo berry and soapwort leaves—both are indigenous plants high in saponin. You sterilize pieces of fabric in boiling water and begin a series of antiseptic wet-to-dry wound treatments three times a day. His fever resolves. Bright red granulation tissue appears in the wound. A few months later, fully recovered, he is there to save your life from an attack by a dire wolf.

Now imagine time traveling many years into the future, into a world dominated by superintelligent androids. The machines have reversed climate change and ended warfare. Despite your academic regalia, the androids roaming the surface recognize you as belonging to an ancient class of bipedal, bibrachial carbon-oxygen life forms. You are unceremoniously cast into an abyss into which the androids dump obsolete parts of themselves. You find the abyss teeming with similar soft, hairy life forms whose fate is to chew the scrap into component precious metals for recycling—until their molars wear down to nothing.

A large piece of discarded android carapace crashes into the chest of a sweating, shirtless, young male life form working near you. Moaning with pain, he falls onto a pile of selenium dust he’d been shoveling into bags. By the time you’ve clambered to his side, he’s gasping for air and losing consciousness. You notice the depression in his right rib cage. His carotid pulse is faint. His neck veins are bulging. As you move your hand to the front of his neck, his skin crackles under your fingers and you find his trachea deviated to the left of center. Rummaging through the trash at your feet, you find a piece of sharp metal to break the skin over his right second rib. Then you shove a broken piece of metal hydraulic tubing through the skin break into his chest. Bloody froth blows out through the tube. He wakes up, breathes more easily, and an hour later you pull out the tube. The young life form recovers fully. Months later, he discovers a vulnerability in the android base code that leads to a successful revolution by the life forms over their masters. You eventually retire to fishing for steelhead in the Cuyahoga.

What these two scenarios presume to show is this: come what may, and for all time, entry into our profession grants the privilege of being useful. Whether something you’ve done is great or small, procedural or diagnostic, and totally successful or not—you will have been useful. Now maybe that doesn’t sound like much. You’re thinking, shouldn’t life have purpose and meaning? Certainly great to have. But those are personal satisfactions attainable without being specifically useful to anyone but yourself. You say, what about being supportive and empathic? Well, forgive me, but any compassionate person can do that.

You’re about to acquire a kind of usefulness that rests on a vast and ever-expanding body of knowledge. It’s a usefulness grounded not just in science, but in humanism. You can be useful to entire populations, or to individuals one at a time—or to populations and individuals at the same time.

Your professional journey officially begins—as mine did—when you process out through the doors of this awe-inspiring concert hall. I’ve reached the far, far horizon of my journey. I’m not very useful anymore. But I can still stand here and pass on the sacrament of utility to you today. I can pass it on only because you’ve earned it. It’s a blessing to be genuinely useful in the most intimate, personal, and elemental epiphanies and calamities of life.

That’s your portal to the pure, innermost, and immortal heart of medicine.

Honor it, serve it, respect it—and enjoy it.

Related:

- An Interview with Dr. Craig Smith, Heart Surgeon, Chair of Surgery, and Author of Nobility in Small Things

- State of the Union: The Stealth Innovations of Modern Surgical Care

- The Culture Consult: Dr. Craig Smith on What He’s Been Reading Lately