When Jeanine Ozoa found out she was pregnant with her son Ethan in 2014, she never imagined she’d be packing up her life four months later to move back home to New York. But when a routine ultrasound showed something wasn’t quite right, she knew she needed to be with family. “They didn’t tell me at that moment,” she says. “They just said, ‘We’re going to do another one, just to check.’”

After a second ultrasound, her doctor confirmed that Ethan’s bowels were outside his belly. “There was a hole in his stomach and certain organs were protruding out,” she explains. The condition is called gastroschisis, a birth defect that causes the baby’s intestines, and sometimes other organs, to form outside the body due to a hole in the abdominal wall.

Coming Home for Care

At the time, Jeanine was living in Florida, far from her mom and support system. “After a few days, I was like, I need to go back home,” she says. “I need support.” A friend who had given birth at Columbia/NewYork-Presbyterian recommended she seek care there. “So I got put with a specialty OB, Dr. Russell Miller. Very nice guy, super cool, and he’s a Knicks fan.”

On January 20, 2015, Jeanine went in for a regular follow-up. That same night, Dr. Miller called her. “He said, [the baby’s] bowels are inflamed. You need to come in. He needs to come out,’” says Jeanine. “So I was like, okay, I guess this is happening.”

Jeanine was admitted that night. Doctors initially attempted an induction, but Ethan’s heart rate began dropping, and Jeanine spiked a fever. “So they said, no, we’re going to do a C-section.”

She didn’t see her son until the next day. “They didn’t even lower the curtain to be like, ‘Hey, look at your baby.’ But I heard him cry, and there was all this commotion,” she remembers. “They took pictures and showed me.”

Ethan had been born with his stomach, small intestine and large intestine outside of his body. But by the next day, everything was back inside. “I don’t know how they did it,” says Jeanine. “But they put everything back. They told me I had a really strong baby because he tolerated it well. He barely cried.”

It was then she named him Ethan, not realizing at the time that it meant ‘to be brave.’ “That is a perfect name for him, given the circumstances,” says Jeanine.

The First Months

Ethan spent a month in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). He had three peripherally inserted central catheters, or PICC lines, to bring him medication and fluids—first in one arm, then the other, and finally in his head after the first two failed. “They shaved half his head to put a PICC line in,” Jeanine recalls. When he was finally discharged, she saw something troubling: “After a week, I noticed he was losing weight instead of gaining.”

Back to the hospital they went.

“His intestines were infected,” she says. “So he had to stay again. He stayed for another month. They were doing blood work all the time, he had all these bruises… blood work here, blood work on his legs, on his feet, from everywhere.”

Eventually, with all of his veins blown, they placed a long-term central venous catheter called a Broviac line in his chest. Doctors also determined that the formula he had been on was contributing to the issue, triggering a cascade of allergies that would follow him for years: milk, peanuts, soy, seafood, even cats and dogs.

Still, says Jeanine, “If you see him, you would never guess anything was ever wrong with him.”

Growing Into Himself

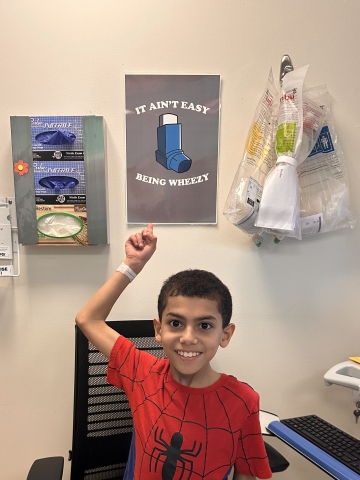

Today, Ethan is ten. He finished fourth grade this year and, according to his mom, gave his whole class an anatomy lesson. “He told them, ‘This was my intestine. It was outside my stomach. This is what the stomach looks like,’ and he pulled it up on the board,” she laughs. “He did a whole medical class.”

He continues to see specialists in GI, pulmonary, and allergy, and he’s had multiple endoscopies and bronchoscopies. “At one point, he was getting them every six months,” Jeanine says. “That’s a lot for anybody.” But he handles it all with a maturity beyond his years. “He’ll be like, ‘No, I can’t eat this,’ or ‘What’s in it?’ He knows. He has his EpiPen, his asthma pump, everything is set. He even tells other people.”

Though Ethan is still on a restricted diet and in the lower weight percentile, things are improving. “He’s been cleared for dairy now. He eats all that stuff.” His growth continues to be monitored, but the outlook is strong.

“His diagnosis was ‘failure to thrive,’ but he is not failing at all. He’s thriving very well.”

A Mother’s Heart Prevails

Jeanine is a Columbia employee now, and part of the Patient Safety Champions program. But long before she joined the staff, she lived inside these walls, first as a patient herself, recovering from a C-section, and then as a full-time NICU mom.

“I was literally here every day, all day. Even when he got readmitted, I couldn’t leave him. I basically lived here,” she says. “My mom brought over his baby swing. I had set up the whole area in the hospital room.”

She washed her clothes on-site, took showers on the children’s floor, and stayed through shift changes. “I took the train to come here. With the stitches and all. My mom was like, ‘Jeanine, you have to stay home.’ I was like, no. My baby’s not even there, what would I do?”

Even though Ethan was a preemie with a Broviac line, his nurses made sure he had clothes that worked with his constraints, little vests and sweaters from their bins of donated outfits on the floor. “They made him a little laundry bag out of a brown paper bag. One of the nurses even did his hair. I came in one morning, and he had a little part swooped to the side,” she smiles. “They were taking such good care of him.”

The hospital even encouraged her to sleep with a stuffed animal so they could place it in Ethan’s incubator. “So he knew that mommy was there,” she says. “I still have that stuffy. I’m never getting rid of it.”

Noble and Brave

Ethan is now the proud older brother of two-year-old Aria. “And her name means ‘noble,’ so now I have ‘noble’ and ‘brave.’ They’re inseparable.” Jeanine says. “When I was pregnant, he said, ‘I want a sister.’ I’ve never heard of a boy asking for a younger sister. But he meant it. And he takes such good care of her.”

Beyond siblinghood, he’s thriving in more ways than one. “He got the highest scores on his state exams,” Jeanine says. “He’s surpassing everything we thought he wasn’t going to make. I look at him now, ten years later, and I think, what if I hadn’t come back to New York? What if he hadn’t been treated here?”

In the NICU, Ethan shared a pod with two other babies. One had the same condition, gastroschisis, but didn’t survive.

“We were all like, ‘Ethan, please. Please, Ethan. You got this,’” Jeanine remembers. “But every nurse, every doctor, anybody that interacted with him said the same thing—‘He’s so strong. He’s so brave. He’s a fighter.’”

Related:

- State of the Union: Pediatric Surgery Today

- Profile in Hope: A New Surgery Helps Improve the Lives of Babies with Spina Bifida

- Tiny Patients, Big Solutions: A Closer Look at Fetal Surgery Innovations