Four operating rooms. A robotic donor surgery. One liver that would be divided to save three adults.

This single day combined:

- A robotic living-donor surgery (a healthy donor donates part of their liver)

- A domino transplant (a chain of organ donations between multiple patients)

- A split-liver transplant (a procedure where a donor liver is split into two parts, with each part transplanted into a separate recipient)

All in adults, all at once.

It stretched across 15 hours, four rooms, and more than 30 team members. And in the end, three patients received the chance at renewed life.

Here’s how it unfolded, step by step, told in sequence with just enough anatomy to bring you into a surgical mindset.

The Warm-Up: From Weeks to Day-Of

This day was months in the making. Doctors ran scans, matched sizes, assigned operating rooms, and mapped out contingency plans in case anything went wrong.

Four rooms, four surgeries. At a glance, who was where:

- OR-Donor: Robotic living-donor liver surgery (performed by Jason Hawksworth, MD and Nathaly Llore, MD)

- OR-Domino/Split: Transplanting the donated piece and removing/splitting the first recipient’s liver (performed by Tomoaki Kato, MD)

- OR-Recipient A: Transplanting part of the split liver (performed by Jean Emond, MD)

- OR-Recipient B: Transplanting the other part (performed by Peter Liou, MD)

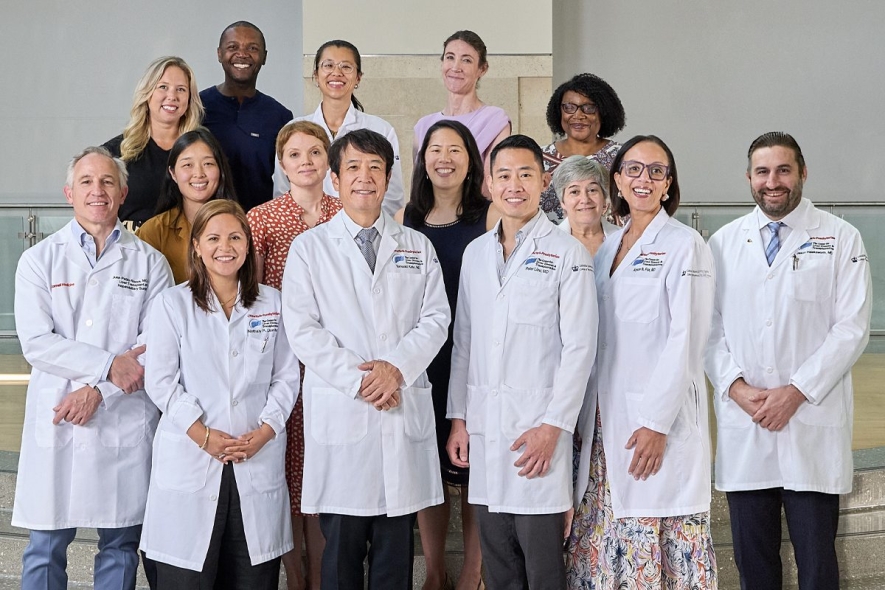

Supporting them: anesthesia, perfusion, nursing, hepatology, genetics, and “back-table” prep teams — more than 30 people in motion.

6:30 AM: Lights Up

Two operating rooms begin simultaneously:

- The donor room, where a robot will help remove about 60% of the donor’s liver through tiny incisions (a procedure known as robotic hepatectomy).

- The domino/split room, where the first recipient is prepped for their transplant.

Meanwhile, the two other recipient rooms ready their patients, inserting lines and opening surgical sites.

Parallel starts shorten the time organs spend outside the body, which is crucial for survival.

8:00 AM: Ports In, Robot Docked

In the donor room, the robot is docked to the small incisions, offering surgeons a magnified, steady view.

Across the hall, surgeons carefully begin to free the first recipient’s diseased liver, working around the vessels that carry blood in and out.

9:30–11:30 AM: Precision and Transection

Surgeons in the donor room isolate veins and arteries, marking safe boundaries before cutting. By mid-morning, they begin dividing the donor’s liver tissue with ultrasonic tools that slice and seal at the same time.

Across the hall, the domino/split team edges closer to removing their patient’s entire liver.

12:30 PM: The First Hand-Off

The donor’s liver portion is freed. On a nearby sterile back table, it is flushed, trimmed, and checked (think of it like a tailor adjusting a suit before it’s worn). Then it is carried next door to be transplanted into the domino recipient.

Surgeons rush because every minute the liver is on ice, its chances of working well shrink.

1:30 PM: The Split—One Liver Becomes Two

The domino recipient’s own liver, though affected by a genetic condition, is structurally healthy. It is removed and carefully divided into right and left portions — each large enough to support an adult.

Those halves are dispatched to the two remaining operating rooms. While this is happening, the donor’s graft is being sewn into the domino recipient.

Splitting adult livers is rare; it requires exact matches between organ size and recipient body size.

2:00–3:00 PM: New Blood Flow

In the two recipient rooms, surgeons connect the new livers vein-first for outflow, then open the portal vein to let blood rush in.

The pivotal moment: reperfusion. The pale grafts “pink up,” signaling that life has returned. Soon after, arteries are connected to provide the full blood supply.

This is the “lights on” moment — the instant the grafts begin working for their new owners.

Late Afternoon: Bile Ducts and Closure

The hardest plumbing is done; now surgeons connect bile ducts so the new livers can drain properly. Some ducts are stitched directly together; others need a small piece of intestine to bridge the gap (this is called a Roux-en-Y).

Bleeding is checked and checked again, in a process called hemostasis. Then, after hours of focus, the final stitches close the abdominal walls. One by one, the rooms finish.

Why This Domino Worked

The first recipient’s disease was a biochemical issue — not structural damage. That meant their liver’s architecture was intact, suitable for others, and large enough to be safely divided into two grafts. Transplanted into people without their condition, the organ functions normally.

Technically, this day combined a robotic living-donor hepatectomy, a domino, and a split, all in adults, all in parallel. Practically, it expanded the donor pool and showed what deliberate planning can achieve. The work spanned roughly 15 hours across four operating rooms with a multidisciplinary team of more than 30 people. The patients are thriving.

Tiny Glossary

- Hepatectomy: Removing part of the liver

- Back table: The prep station where grafts are flushed and trimmed

- Explant/Implant: Taking out a diseased organ / putting in a donor organ

- Anastomosis: Sewing vessels or ducts together

- Reperfusion: Restoring blood flow to a new organ

- Roux-en-Y: A bile duct connection using a piece of intestine

- Regeneration: The liver’s ability to regrow to the size the body needs

Related:

- One Living Donation Saves Three Lives: NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia Performs the First Domino Split-Liver Transplant in Adults in the U.S.

- Changing the Future of Living Liver Donation: A Conversation about Columbia’s All-Robotic Approach

- A Look Inside the 24-hour Dance of a Split-Domino Heart Transplant