An interview with plastic surgeon Jarrod T. Bogue, MD and Katherine Satriano, Head of Archives and Special Collections at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, on their mutual passion project—a historical research paper about Jerome P. Webster, the "father of plastic surgery education," recently published in the Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery.

Dr. Bogue, what first drew you into Webster’s work and this project?

Dr. Bogue: I’ve personally always had an interest in history. I minored in it in college, and all my kind of pleasure reading is in the history realm. Columbia obviously has a really rich medical history, being an institution that’s been around for a long time. A lot of major discoveries have happened here.

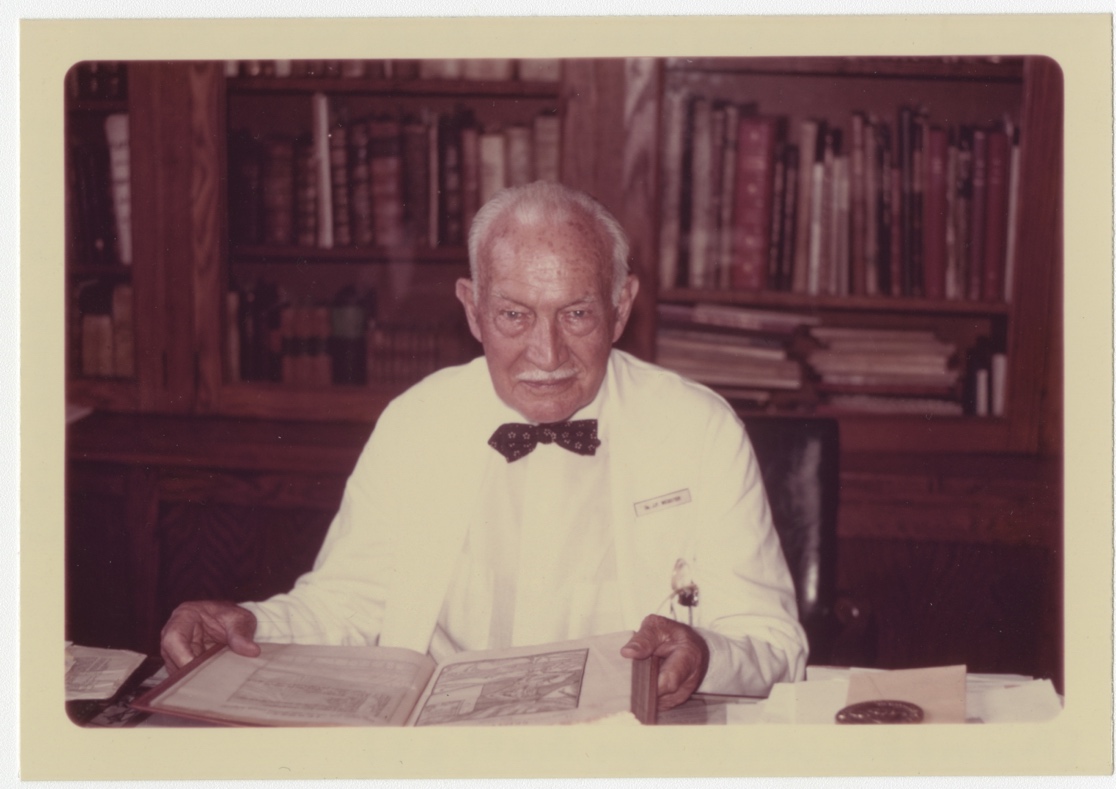

Being part of the Columbia community, I had heard about Jerome Webster in the past. He was the first chief of plastic surgery at Columbia. He was recruited by Dr. Whipple to come and establish plastic surgery here, and Webster was a huge figure in early plastic surgery in America. He started the first plastic surgery training program, was one of the first presidents of the American Board of Plastic Surgery, and I think he started the American Association of Plastic Surgery as well.

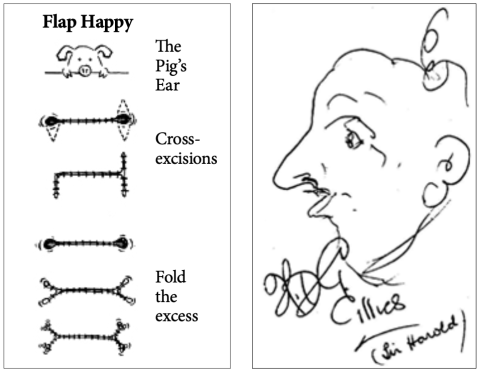

He’s really this instrumental figure. One of the seminal texts of early plastic surgery was written by Sir Harold Gillies, and Webster wrote the foreword. He’s a giant in the field.

What makes the Webster Collection at Columbia so unique?

Katherine Satriano: We say it’s perhaps the most comprehensive collection about plastic surgery in the world. Webster collected it and donated it. The Webster Collection is enormous—347 boxes of his papers, plus 119 cartons and 12 document boxes of patient photographs.

And then for the sketchbooks alone, there are 7.25 boxes, about two and a half feet. It’s this really visually striking, comprehensive archive, and it’s been amazing to see people use it.

Tell us about the sketchbooks you analyzed for this recent paper.

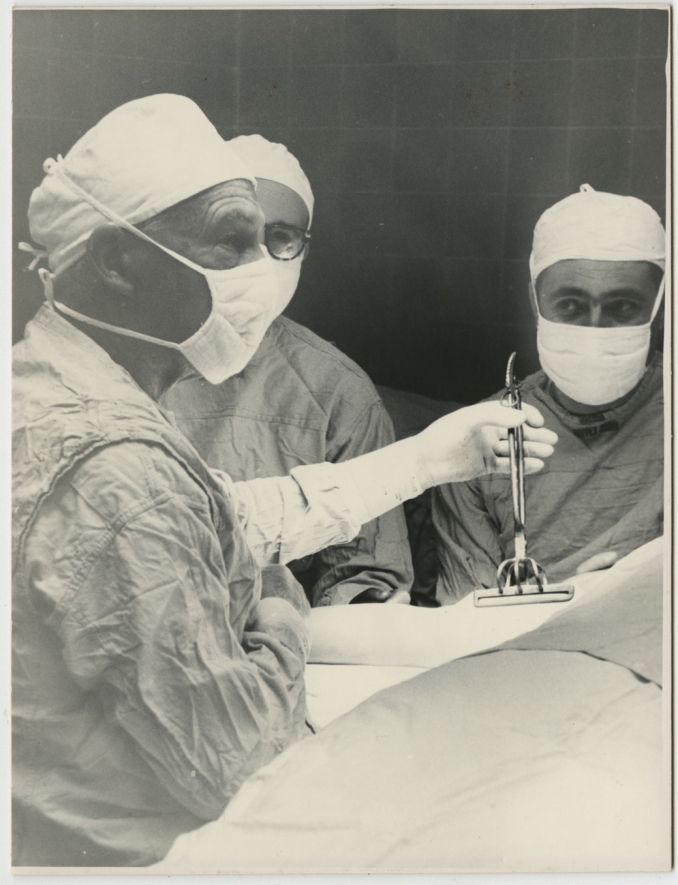

Dr. Bogue: Webster had a medical illustrator for most of his surgical cases, someone drawing everything happening live in the OR. So we went through five years of his sketchbooks, from 1943 to 1948, and categorized what kinds of cases he was doing. Craniofacial cases, nasal cases, extremity cases—we basically mapped the landscape of what plastic surgery looked like then.

We thought that timeframe was interesting because it was during and just after World War II, and Webster was very settled in practice by then.

What stood out to you in the cases?

Dr. Bogue: The big thing is the lack of microsurgery. Today, I can move tissue by disconnecting it and reconnecting blood vessels. Webster didn’t have access to that. So he relied on something Gillies invented and Webster championed—the walking tube flap.

There was one case with bilateral foot wounds where Webster walked a flap from the thigh of one leg onto both feet. It took four different operations over about a year. That kind of multi-stage improvisation was state-of-the-art at the time.

Katherine, what has it been like supporting this research from the archives side?

Katherine Satriano: It’s been really exciting. I think it’s wonderful that there’s such a strong appreciation of the field’s history and what it means today. Medical students have been involved, and it’s interesting for them to think about what they can learn from the past and how that influences practice now.

I’m hoping others will also make use of the collection; it’s a rich resource.

Beyond the sketchbooks, what else is in the collection that excites you?

Dr. Bogue: There’s so much. Early medical photography, surgical instruments Webster had made based on 16th-century drawings, even a prescription signed by Tagliacozzi, a Renaissance surgeon.

Katherine Satriano: And there’s film—67 small reels and five large reels—likely of plastic surgery patients at Columbia Presbyterian from 1942 to 1963. We don’t know if it’s before-and-after footage or operations in progress, but digitizing it could be incredible.

How do you envision sharing this history more broadly?

Dr. Bogue: We’d love to do more. A series of posts, an exhibit at the library, maybe even a talk. The volume of material is amazing.

Katherine: Yes! We have an exhibit case at the library that could showcase this, and we can also feature work on our website. And if there’s funding, digitizing the film would be extraordinary.

Dr. Bogue, you mentioned international work as well. How does that connect to Webster’s legacy?

Dr. Bogue: Webster did charitable work in China in the 1920s and ’30s to teach plastic surgery, and we’ve written a manuscript about that. For me, I also do international work, teaching microsurgery in Ethiopia. That’s a strong tradition in plastic surgery: spreading knowledge and training globally.

Closing Thoughts

Katherine Satriano: This has been a really collaborative project. The Webster Collection has so much to offer, and I’m excited to see it continue to inspire research and education.

Dr. Bogue: Agreed. We’ve only scratched the surface, and I think there’s a lot more to uncover.

Related:

- The Modern International Surgical Mission Starts Local and Stays Local

- History of Medicine: Whipple's Improvised Breakthrough

- Orthoplastic Surgery: Function Follows Form

Subscribe to Healthpoints and never miss an update.