"Ninety percent of these operations are planning. Maybe 10 or 20 percent is execution."

Over the last several years, aortic surgery has evolved greatly. Endovascular techniques have expanded; imaging and device technology have advanced. And surgeons are learning more about the biology of aneurysms themselves. This knowledge is beginning to change not just how repairs are performed, but how long patients live afterward.

In this State of the Union conversation, Virendra Patel, MD, MPH, Chief of Vascular Surgery and Co-Director of the Aortic Center, reflects on how aortic care has changed in recent years, why Columbia continues to push the boundaries of complex endovascular repair, and what it takes to balance innovation with safety, training, and lifelong patient relationships.

From Open Surgery to an Endovascular-First Approach

Back in 2022, we talked a lot about hybrid approaches and early endovascular strategies. Over the last couple of years, has anything shifted in how you think about treating the aorta?

Editorial note: Hybrid strategies are a treatment approach that combines traditional open surgery with catheter-based endovascular techniques. Endovascular strategies are minimally invasive, catheter-based treatments (such as stent graft placement) delivered through blood vessels to repair or reinforce the aorta without open surgery.

I think we’re more aggressive about endovascular now. It’s minimally invasive, patients recover faster, the operations are faster, and they’re less physiologically stressful for patients.

Historically, endovascular had a higher risk of failure, mostly because of all the components and pieces that have to come together to treat a complex aorta endovascularly. But what we’ve learned, through our own research and that of others, is that if you can manage what’s happening in the aneurysm sac, which is the space outside of the stent, outcomes improve.

Will you expand on that?

We now actively try to address that space by filling the aneurysm sac with plugs or reducing blood flow into it by coiling off small branches that would otherwise continue to feed the aneurysm after the stent is placed. We’re finding that doing this increases durability and improves survival.

Whereas in 2022 I probably thought of myself as an open surgeon first—and only considered endovascular when open surgery wasn’t an option—I now think of patients as equally treatable with both approaches.

Is that shift mostly about advances in technology, or is it also about understanding aortic disease differently?

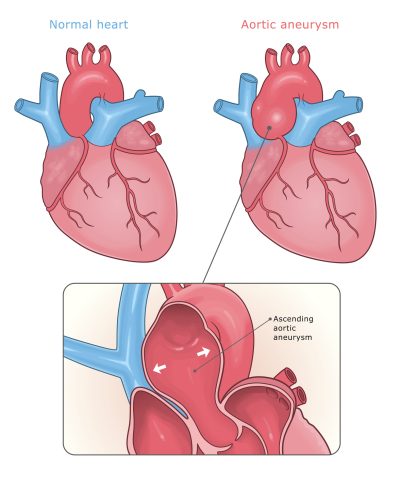

It’s both. When you fix an aneurysm with a stent, you’re basically relining the pipe from the inside. But an aneurysm isn’t just a pipe—it’s a bubble. And that bubble sits outside the stent.

Blood continues to pass through that space, and it’s biologically active. There’s chronic inflammation, clot formation, immune cells living in that aneurysm sac. All of that impacts the patient.

Dr. Tom O’Donnell and I have done a lot of research looking at sac behavior after aneurysm repair. What we found is that if the sac shrinks, meaning the aneurysm collapses down onto the stent, those patients live the longest. If the aneurysm doesn’t change, or worse, continues to grow, survival is worse.

That finding holds true across multiple aneurysm types—thoracoabdominal grafts, thoracic grafts—it’s remarkably consistent. So now there’s a huge push not just to place a stent, but to actively treat the aneurysm itself.

The Shape Memory Trial and a New Endovascular Frontier

Let’s pivot to clinical trials—what’s important to know?

Yes. Right now, there’s one called the AAA Shape trial. It’s a randomized controlled study comparing standard stent repair versus stent repair plus filling the aneurysm sac with foam plugs made by Shape Memory Medical.

I’m one of the international principal investigators, along with Mark Shermerhorn and Ross Milner. The trial will enroll 160 patients, randomized two-to-one, so two patients get plugs for every control.

We’ve already reached over 100 patients, and we expect the trial to complete enrollment this spring. If we can show that the sac reliably shrinks in patients treated with plugs, it could fundamentally change how we approach endovascular repair.

Wow. It sounds like this approach has already been a part of how you determine aneurysm repair now.

It is. At Columbia, we already firmly believe the sac is part of the problem. We’ve been filling aneurysm sacs since around 2022, when the plugs became commercially available. Our preliminary data suggests 60–70 percent of patients now see aneurysm shrinkage, compared to about 40 percent historically.

We’re also collecting blood from trial patients to look for biological markers that might predict who responds best—whether there are genetic or inflammatory signatures that correlate with sac regression. As a PI, I don’t get to see the randomized data mid-trial. But our own non-randomized experience suggests patients are better off.

Pushing the Envelope in Complex Endovascular Repair

How does this translate into the kinds of cases you’re taking on now?

We’re definitely pushing the complex aneurysm envelope. We’re doing aortic arch aneurysms endovascularly. If a patient already has an ascending graft from open heart surgery, we can use that graft as an anchor and build everything below it endovascularly.

Some patients still absolutely need open surgery—young patients, those with connective tissue disorders, or active infections. But when it’s a toss-up between open and endovascular, we’re leaning more toward endovascular because we now have the tools and experience to make the anatomy work.

We can modify small segments of the aorta to create landing zones for stents. We can reroute important blood vessels. We can do hybrid procedures. It’s very creative work. No two patients are the same. We look at the anatomy, decide where stents need to go, how many branches we need, where fenestrations belong [openings created surgically to improve blood flow or function], and then we execute.

Vascular Surgeon Draws on the Art of Surgery in His Own Way

How much of this comes down to planning?

Ninety percent of these operations are planning. Maybe 10 or 20 percent is execution.

We use advanced 3D reconstruction software to study every patient’s anatomy. We measure branch vessels, diameters, angles. We identify exactly where everything needs to go. We also have biweekly aortic imaging conferences where surgeons, nurse practitioners, residents, fellows, and radiologists review cases together. We decide who needs follow-up, who needs preparation, and what approach makes the most sense.

Dr. O’Donnell now pre-plans many cases, which helps enormously. I’ll review his work, tweak measurements based on experience, adjust where fenestrations should go, and finalize the device orders. It used to take me weeks to prepare some cases. Now, much of that groundwork is already done.

With the Aorta, Surveillance Is Care

A lot of this feels like preventative care too. How do you think about long-term treatment for these patients?

Aortic care is lifelong. We work closely with cardiology and cardiogenetics, especially for younger patients or those with connective tissue disorders. And we follow our own patients annually or biannually, depending on pathology. We also run a nurse practitioner surveillance clinic every week. Patients can do video visits, review scans, and get guidance without traveling into the city. It saves them trips but always keeps us closely involved.

Not every aneurysm needs to be fixed right away. Size, growth rate, genetics, blood pressure, lung disease—all of it matters. Guidelines help, but every decision is individualized.

Is every aneurysm treated with this type of nuance?

Absolutely. Some patients technically meet size criteria but have advanced cancer or other serious illnesses. Fixing the aneurysm wouldn’t improve their overall outcome. Others have small aneurysms but are so anxious that their blood pressure rises just thinking about it. In those cases, early intervention might actually help.

It’s granular. We follow patients; we advise them. And we fix things when it’s appropriate.

Access, Volume, and Structural Barriers

If you could change one structural thing about aortic care in the U.S., what would it be?

Well, high-volume centers do better. That’s just reality. But we work in a fee-for-service system, and insurance restrictions often prevent patients from getting to the centers best equipped to treat them. New Jersey patients, for example, may be physically closer to us but unable to cross the river because of insurance.

Regionalization of complex care would improve outcomes, but it also creates hardships for families who can’t afford to travel or stay in New York.

It’s a difficult balance. Quality improves with volume, but access becomes harder. So first would be access.

Training the Next Generation

What does this evolution in approaches to the aorta mean for surgical training?

You know, that’s one of my biggest concerns. I now do about 80 percent of aneurysms endovascularly and only 20 percent open. Even at a high-volume center like ours, open experience is declining. Nationally, graduating residents may see only one or two open aortic repairs during training. At Columbia, our fellows see closer to 20–30. That difference matters.

If someone shows up to a community hospital with a ruptured aneurysm in 10 or 20 years, I worry there won’t be enough surgeons with the experience to fix it.

We need dedicated training centers to preserve open surgical skills. We also need multidisciplinary programs where vascular and cardiac surgeons collaborate instead of competing. There are no turf wars here. We don’t draw lines in the sand over arteries. We work together and prioritize that always. That culture matters greatly.

If we have this conversation again in five or ten years, what do you hope will be different?

I hope we’ll have multiple commercially available devices that can be used across a wide range of anatomies. And I hope we continue publishing outcomes so other centers can learn from high-volume experience. I hope we preserve open surgical training and continue building collaborative, multidisciplinary programs.

Because at the end of the day, this is about giving patients the best possible care—whether that means innovation, restraint, or simply taking the time to plan every detail before ever entering the operating room.

Related:

- State of the Union: Vascular Surgery Today

- Vascular Surgeon Draws on the Art of Surgery in His Own Way

- Dr AI: I Have an Aortic Aneurysm; Can I Go to the Gym?